Training and Safety Main Header

Training and Safety

Pilot licenses, training requirements, where to train for your pilot licence, ideas to keep you flying and developing your flying skills, if it goes wrong, find an instructor or examiner to keep you flying.

Training

Training

Flight Training

Find out More

Online Learning

Find out More

Aerobatic rating

Find out More

FI Refresher Course

Find out More

Radio Navigation Certificate

Find out More

Ground Instructor Certificate

Find out More

Flying Companions Course

Find out More

Safety

Safety

AOPA Strasser Scheme

Find out More

UK Distress and Diversion

Find out More

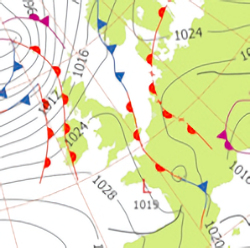

Weather Services

Find out More

Personal Minimums

Courtesy AOPA USA

Training and Safety Information

Information

Pilot Tips

Emergency Procedures

Occurrence Reporting

UK CAA Infringement Process